01 Basics

- Magnetism

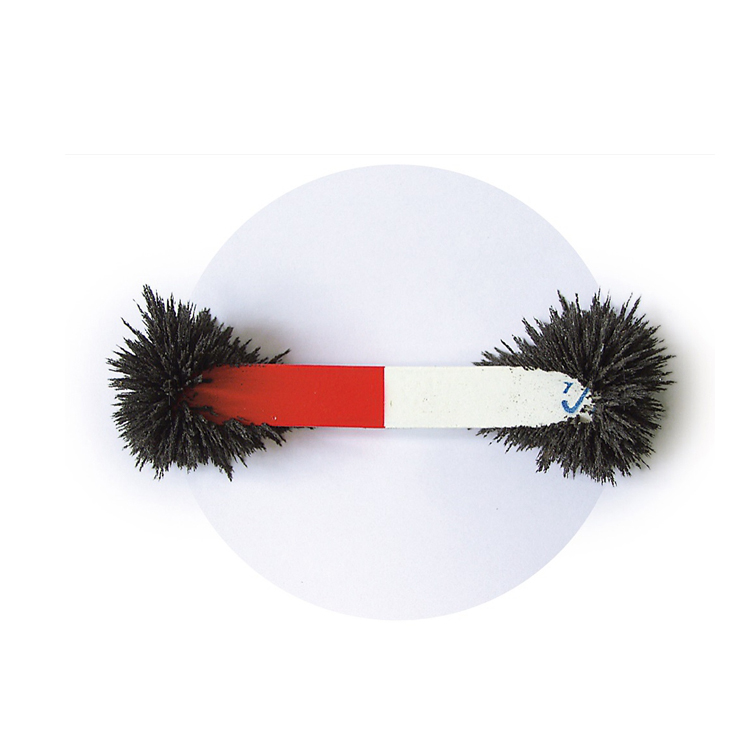

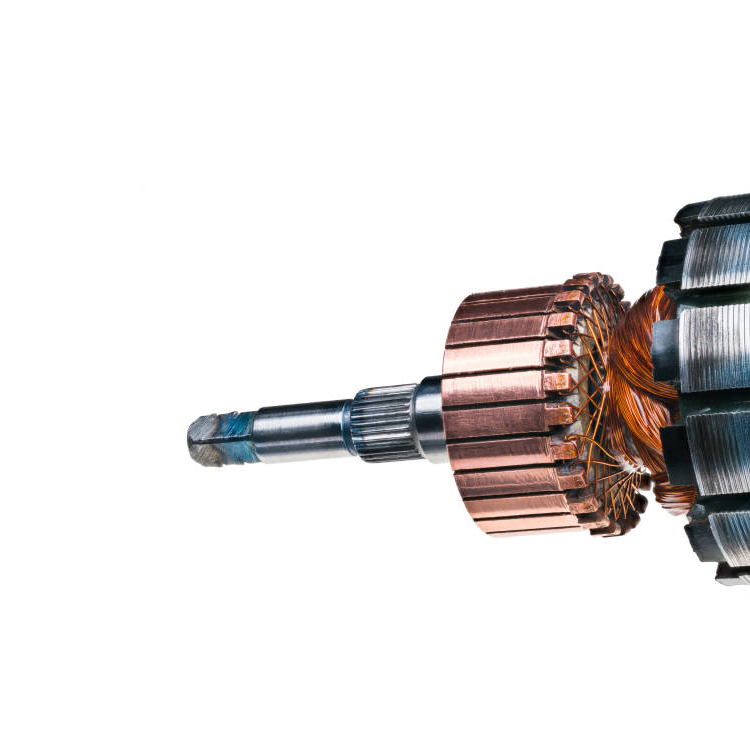

Magnetism is a fundamental physical property of matter, characterized by the ability to generate a magnetic field and interact with it. Magnetic materials (such as iron, cobalt, nickel, and their alloys) are attracted or repelled in a magnetic field due to the microscopic magnetic moments arising from the spin and orbital motions of electrons within the material. Based on magnetization behavior, materials can be classified as ferromagnetic, paramagnetic, diamagnetic, etc. Among these, permanent magnetic materials like neodymium iron boron (NdFeB) are widely used in motors, sensors, and other fields due to their strong ferromagnetism. Magnetic phenomena not only underpin modern power electronics technology but also provide a key window into understanding the quantum properties of materials.

- Magnetic Materials

- Soft Magnetic Materials: These materials achieve high magnetization with a relatively small external magnetic field. They feature low coercivity and high permeability, making them easy to magnetize and demagnetize. Examples include soft ferrites and amorphous/nanocrystalline alloys.

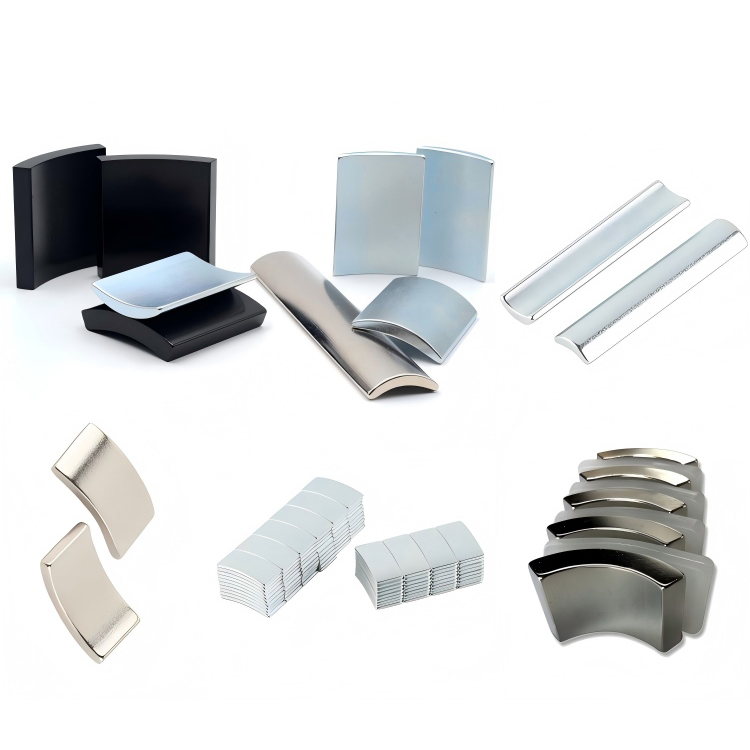

- Hard Magnetic Materials: Also known as permanent magnetic materials, these are difficult to magnetize but once magnetized, they retain their magnetism effectively. They are characterized by high coercivity and include rare-earth permanent magnets, metallic permanent magnets, and permanent magnet ferrites.

- Functional Magnetic Materials: This category includes magnetostrictive materials, magnetic recording materials, magnetoresistive materials, magnetic bubble materials, magneto-optical materials, and magnetic thin films.

- NdFeB Permanent Magnet Materials

- Sintered NdFeB: Produced using powder metallurgy technology, where the alloy is melted, pulverized into powder, compacted under a magnetic field, and then sintered in an inert gas or vacuum to achieve densification. Aging heat treatment is typically applied to enhance coercivity, followed by machining and surface treatment to obtain the final product.

- Bonded NdFeB: Formed by mixing permanent magnet powder with a flexible binder such as rubber or lightweight rigid plastic, then molded directly into various shapes according to customer requirements.

- Hot-Pressed NdFeB: Achieves magnetic properties comparable to sintered NdFeB without the need for heavy rare-earth elements. It offers high density, high orientation, good corrosion resistance, high coercivity, and near-net shaping. However, it has relatively poor mechanical properties, and due to patent restrictions, processing costs are higher.

- Remanence (Br)

Remanence refers to the magnetic induction intensity retained by a magnet after being magnetized to technical saturation in a closed circuit and then removed from the external magnetic field. In simple terms, it can be understood as the magnetic force of the magnet after magnetization. Its units are Tesla (T) and Gauss (Gs), with 1 Gs = 0.0001 T. - Coercivity (Hcb)

Coercivity is the value of the reverse magnetic field strength required to reduce the magnetic induction intensity of a magnet to zero during reverse magnetization. At this point, the magnetization intensity of the magnet is not zero; rather, the applied reverse magnetic field counteracts the magnetization intensity. If the external field is removed at this stage, the magnet still retains some magnetic properties. Unit conversion: 1 A/m = (4π/1000) Oe, 1 Oe = (1000/4π) A/m. - Intrinsic Coercivity (Hcj)

Intrinsic coercivity is the reverse magnetic field strength required to reduce the magnetization intensity of a magnet to zero. Magnetic material grades are classified based on their intrinsic coercivity levels: low coercivity (N), medium coercivity (M), high coercivity (H), extra-high coercivity (UH), extremely high coercivity (EH), and ultra-high coercivity (TH). - Maximum Magnetic Energy Product (BH)max

This represents the magnetic energy density established between the two poles of a magnet, i.e., the magnetostatic energy per unit volume in the air gap. It is the maximum product of B and H and directly indicates the performance level of the magnet. Under identical conditions (same size, same number of poles, same magnetization voltage), magnets with a higher (BH)max achieve higher surface magnetism. However, for the same (BH)max value, the levels of Br and Hcj influence magnetization as follows:

- High Br, low Hcj: Higher surface magnetism can be achieved with the same magnetization voltage.

- Low Br, high Hcj: A higher magnetization voltage is required to achieve the same surface magnetism.

- SI Units and CGS Units

The International System of Units (SI) and the Gaussian System of Units (CGS) are two different measurement systems. The conversion between them is relatively complex, akin to the difference between “meters” and “miles” in length units. - Curie Temperature

The Curie point is the critical temperature at which a magnetic material transitions from ferromagnetism to paramagnetism. Below the Curie point, the material exhibits ferromagnetism, and its internal magnetic field is difficult to alter by an external magnetic field. Above the Curie point, the material becomes paramagnetic, and its magnetic field easily changes with an external field. The Curie point represents the theoretical upper limit of the working temperature for magnetic materials. For NdFeB, the Curie point ranges between 320°C and 380°C, depending on the crystal structure of the magnet. Once the Curie point is reached, molecular activity within the magnet intensifies, leading to demagnetization, which is irreversible. Demagnetized magnets can be re-magnetized, but their magnetic force is significantly reduced, typically recovering only about 50% of the original strength. - Operating Temperature

The maximum operating temperature of sintered NdFeB is much lower than its Curie point. Within the operating temperature range, magnetic force decreases as temperature rises, but most of it can recover upon cooling. A higher Curie point generally allows for a higher operating temperature and better temperature stability. Adding elements such as cobalt, terbium, or dysprosium to sintered NdFeB can raise its Curie point, which is why high-coercivity products often contain dysprosium. The maximum usable temperature of sintered NdFeB depends on its magnetic properties and the operating point selection. For the same magnet, the more closed the magnetic circuit, the higher its maximum usable temperature and the more stable its performance. Therefore, the maximum usable temperature of a magnet is not fixed but varies with the degree of magnetic circuit closure. - Magnetic Orientation

Magnetic materials can be classified as isotropic or anisotropic. Isotropic magnets exhibit the same magnetic properties in all directions and can attract indiscriminately. Anisotropic magnets, however, have varying magnetic properties in different directions, with the optimal magnetic performance occurring along the orientation direction. For example, in a rectangular sintered NdFeB magnet, the magnetic field strength is strongest along the orientation direction and weaker along the other two directions. If a magnetic material undergoes orientation treatment during production, it is anisotropic. Sintered NdFeB is typically formed by magnetic field orientation pressing, making it anisotropic. Prior to production, the orientation direction—the future magnetization direction—must be determined. Powder magnetic orientation is one of the key technologies for manufacturing high-performance NdFeB. (Note: Bonded NdFeB can be either isotropic or anisotropic.) - Surface Magnetic Field

This refers to the magnetic induction intensity at a specific point on the surface of a magnet (which varies between the center and edges). It is measured by placing a Gauss meter in contact with a particular surface of the magnet and does not represent the overall magnetic performance of the magnet. - Magnetic Flux

In a uniform magnetic field with magnetic induction intensity B, if there is a plane with area S perpendicular to the magnetic field direction, the product of B and S is called the magnetic flux through that plane, denoted as “Φ” and measured in Weber (Wb). Magnetic flux is a scalar quantity representing the distribution of the magnetic field, though it has a positive or negative sign to indicate direction. The formula is Φ = B·S. When the plane is at an angle θ to the perpendicular direction of B, the formula becomes Φ = B·S·cosθ. - Electroplating

Sintered NdFeB permanent magnet materials, produced via powder metallurgy, are highly chemically active and contain microscopic pores and voids, making them susceptible to corrosion and oxidation in air. Therefore, thorough surface treatment is essential before application. Electroplating, a widely used metal surface treatment technology, is commonly employed for NdFeB magnets. The most common electroplating layers for NdFeB magnets are zinc plating and nickel plating, which differ significantly in appearance, corrosion resistance, service life, and cost:

- Polishing Effect: Nickel plating offers a brighter, more polished appearance compared to zinc plating. Products with high aesthetic requirements typically use nickel plating, while magnets not exposed to view often use zinc plating.

- Corrosion Resistance: Zinc is an active metal and reacts easily with acids, resulting in relatively poor corrosion resistance. Nickel plating provides stronger corrosion resistance.

- Service Life: Due to differences in corrosion resistance, zinc-plated magnets generally have a shorter service life than nickel-plated ones, often manifesting as coating detachment over time, leading to magnet oxidation and degraded magnetic performance.

- Hardness: Nickel plating is harder than zinc plating, offering better protection against damage from impacts, such as chipping or cracking.

- Cost: Zinc plating is more cost-effective, with prices generally increasing in the order of zinc plating, nickel plating, and epoxy resin coating.

- Single-Sided Magnets

All magnets have two poles. However, in some applications, magnets with only one pole exposed may be required. To achieve this, an iron sheet is often used to cover one side of the magnet, shielding its magnetic field on that side. Such magnets are referred to as single-sided magnets or single-sided magnetic materials. In reality, truly single-sided magnets do not exist.

02 Advanced Topics

- Hysteresis Loop

Hard magnetic materials (such as NdFeB magnets) have two notable characteristics: first, they can be strongly magnetized under an external magnetic field; second, they exhibit hysteresis, meaning they retain their magnetization even after the external field is removed. The curve depicting the relationship between magnetic induction intensity B and magnetizing field strength H for hard magnetic materials is called the hysteresis loop. - Demagnetization Curve

When the magnetic field is reversed from O to –Hc, the magnetic induction intensity B drops to zero. This indicates that a reverse magnetic field must be applied to eliminate remanence. Hc is called coercivity, and its magnitude reflects the ability of the magnetic material to retain remanence. The purple segment in the curve is referred to as the demagnetization curve. - Intrinsic Curve and Squareness Ratio

The inherent magnetic induction intensity generated when a permanent magnet material is magnetized under an external magnetic field is called the intrinsic magnetic induction intensity Bi, also known as magnetic polarization intensity J. The curve describing the relationship between Bi (J) and magnetic field strength H reflects the intrinsic magnetic properties of the permanent magnet material and is called the intrinsic demagnetization curve, or simply the intrinsic curve. When the magnetic polarization intensity J on the intrinsic demagnetization curve is zero, the corresponding magnetic field strength is termed the intrinsic coercivity Hcj. - Surface Treatment – Phosphating

Sintered NdFeB magnets are prone to oxidation and corrosion in air without surface treatment. When these magnets are exposed for extended periods during transportation and storage, and subsequent treatment methods are undetermined, phosphating is often used as a temporary anti-corrosion measure. The phosphating process typically involves: degreasing → cleaning → acid washing → cleaning again → surface adjustment → phosphating → sealing and drying. Currently, commercial phosphating solutions are predominantly used for this process. After phosphating, the product exhibits uniform color and a clean surface. Vacuum packaging can significantly extend storage time, offering an advantage over traditional oil immersion or oil coating methods. - Surface Treatment – Electrophoretic Deposition

Electrophoretic coating technology involves immersing components into a tank containing a water-soluble electrophoretic paint, with an anode and cathode placed in the tank. A direct current is applied to uniformly deposit the water-soluble paint (typically a polymer resin such as epoxy) onto the component surface, forming an anti-corrosion coating. Electrophoretic coatings adhere strongly to the porous magnet surface and offer excellent resistance to corrosion from salt spray, acids, alkalis, and other corrosive agents. However, their performance under damp-heat conditions is relatively poor. - Surface Treatment – Parylene Coating

Parylene, a polymer protective material, can form a protective layer via vapor deposition in a vacuum. Its active molecules penetrate the internal and bottom areas of components, creating a pinhole-free, uniformly thick, transparent insulating coating that provides comprehensive protection against acids, alkalis, salt spray, mold, and various corrosive gases. Parylene’s unique preparation process and outstanding performance enable complete coating of small and ultra-small magnetic materials without weak points. Magnets coated with Parylene can withstand immersion in hydrochloric acid for over 10 days without corrosion. Currently, many small and ultra-small magnetic materials internationally use Parylene as an insulating and protective coating. - Dimensional Tolerances

Tolerance, or dimensional tolerance, refers to the acceptable range of variation in the dimensions of a part during mechanical processing. For magnetic materials, a certain degree of dimensional variation is permissible. Tolerance is defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum allowable dimensions or between the upper and lower deviation limits. - Geometric Tolerances

Geometric tolerances, also known as form and position tolerances, encompass shape tolerances and positional tolerances. All mechanical parts are composed of basic elements such as points, lines, and surfaces. After machining, there is always some deviation between the actual elements and the ideal elements, including shape errors and positional errors. These errors may affect the performance of mechanical products, so corresponding tolerances should be specified during design and marked on drawings according to established standards. - Neutral Salt Spray Test (NSS)

The salt spray test is an environmental test primarily used to evaluate the corrosion resistance of products or metal materials by simulating a salt spray environment in a testing apparatus. It is divided into neutral salt spray and acid salt spray tests, differing in compliance standards and testing methods, also known as NSS and CASS tests, respectively. For sintered NdFeB, the neutral salt spray test is conducted according to national standards using continuous spray. Test conditions include: temperature 35°C ± 2°C, 5% ± 1% NaCl solution (by mass fraction), pH of collected salt spray settling solution between 6.5 and 7.2. The placement angle of the specimen affects test results, with specimens positioned at an angle of 45° ± 5° in the salt spray chamber. - Damp-Heat Test

The damp-heat test for sintered NdFeB is an accelerated simulation method to evaluate the durability of samples in a humid and hot environment. In this test, samples are exposed to high humidity and high temperature for an extended period. Specific test conditions include: temperature controlled at 85°C ± 2°C, relative humidity maintained at 85% ± 5%, using distilled or deionized water as the humidification source. The severity level of the test is set to Grade 1, with a duration of 168 hours. - Pressure Cooker Test (PCT)

The Pressure Cooker Test, also known as the saturated steam test, aims to evaluate the moisture resistance of samples by exposing them to high temperature, high humidity, and high pressure. The PCT for sintered NdFeB involves placing samples in a high-pressure apparatus containing distilled or deionized water with a resistivity exceeding 1.0 MΩ·cm. - Hardness and Strength

Hardness refers to a material’s ability to resist indentation by a foreign object in a localized area and is an indicator of material hardness. The level of hardness reflects the material’s resistance to plastic deformation. Strength, on the other hand, refers to the maximum force a material can withstand under external loads without failure. Based on the form of external force, strength can be categorized as follows:

- Tensile Strength: The strength limit when the external force is tensile.

- Compressive Strength: The strength limit when the external force is compressive.

- Flexural Strength: The strength limit when the external force is perpendicular to the material’s axis, causing it to bend.

- Fracture Toughness

Fracture toughness typically reflects the strength of a material when cracks propagate within it, measured in MPa·m¹/². Testing fracture toughness requires equipment such as a tensile testing machine, stress sensors, extensometers, and signal-amplifying dynamic strain gauges. Additionally, specimens must be prepared in thin sheet form. - Impact Strength (Impact Fracture Toughness)

Impact strength measures the energy absorbed by a material during fracture under impact stress, with units of J/m². The measured value of impact strength is highly sensitive to factors such as specimen size, shape, machining accuracy, and testing environment, leading to relatively large data dispersion. - Flexural Strength

Flexural strength is measured using the three-point bending method to determine a material’s resistance to bending fracture. Due to the ease of specimen preparation and simplicity of measurement, it is most commonly used to describe the mechanical properties of sintered NdFeB magnets.